Folly: Chateau Mathieu Exhibition

I have been focusing on research and work based on the experimental residency that I attended with five other colleagues at the Château Mathieu in Normandy during June 2009. My initial interest was in the matrilineal legacy of the château itself, to explore ideas of the private and public as they applied to women during the Victoria era. Within wealthy families women were, for the most part, relegated to the private sphere of the home where they spent their time embroidering in the sitting room and entertaining guests at the piano. The other area of permitted activity was around the garden and botany. Responding to specific sites at the château, the chapel, garden, grounds and domestic spaces, it was my intention to use embroidery, as well as materials related to opulent domestic interiors of these “ladies of leisure,” in a subversive way to speak about these women’s isolation, lack of agency and stifled creativity.

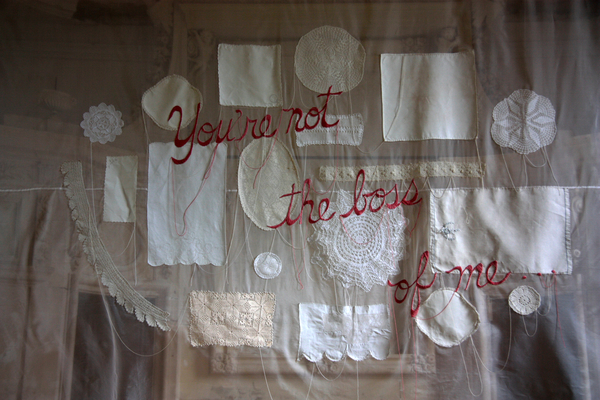

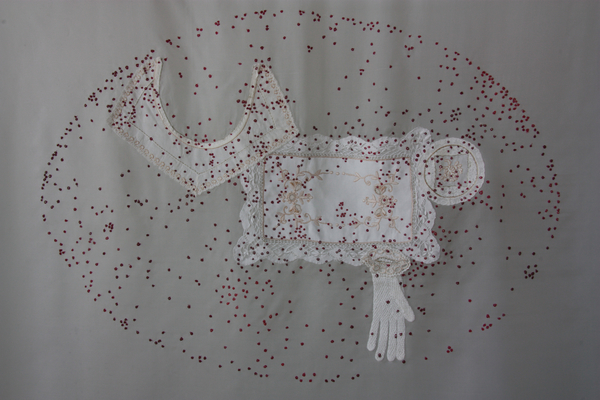

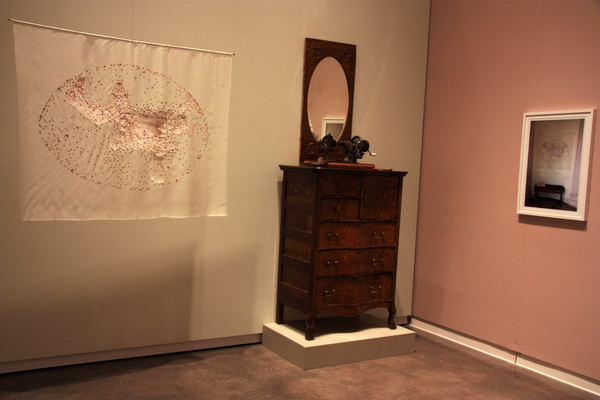

At the Château Mathieu I installed pieces I had brought that were hand-embroidered, antique articles of clothing such as a small girl’s apron and a woman’s lace collar referring to women’s domestic role and lack of agency within the family. Some pieces referred to specific entries in the diary of the château’s matriarch, Jeanne Clarisse Henry. We All Fall Down was based on an excerpt that spoke of several local children that had died of illnesses easily preventable today. At the very same time as the making of this work, the H1N1 virus had gone viral bringing attention to the fact that globalization makes the spread of disease infinitely more likely. The embroidery’s ovoid shape might reference the globe with various red dots marked on it, as well as the physical appearance of red measles. I installed Boss, a large textile with numerous doilies and lace attached to it, in both the chapel and the grand salon. Emblazoned upon the piece was large handwritten text embroidered in pink thread that read You’re not the boss of me, a contemporary female voice not willing to answer either to God or her patriarchal oppressors. Other experiments at the château involved decorating different interior spaces and objects with lace, as well as installing a damaged tablecloth in one of several dining rooms. An embroidered flower motif filled a gaping hole in the tablecloth.

Perhaps the most enlightening creative endeavors came during the latter half of the residency. These evolved out of an intuitive process in which the end result was unknown and would only be revealed through experimentation. In essence, I became engaged in a series of site-specific interventions in the garden and on the grounds of the château. My first exploration was to take thin lace ribbon and wrap it obsessively around the tangled vines of a climbing rose. I then took antique French tapestry fabric adorned with flowers and plants and rich velvets out to the meadow where the sheep were grazing. There I looked at the centuries-old majestic trees, and began my foray into exterior decorating.

These outdoor activities brought to mind feminist cybernetic theorist Sadie Plant’s discussion of women and botany in her book Zeros and Ones. She wrote:

By the mid-nineteenth century ‘a well-established dictum that the study of botany would keep women virtuous and passive.’ They thought this was a fitting discipline for those in need of innocent and moderate intellectual stimulation. Women were not to be trusted with experiments on social animals: plants were most appropriate. Sketching flowers and collecting specimens in chaperoned country meadows seemed innocuous enough and soon the association was so strong that it was even considered ‘unmanly’ in some circles for men to take an interest in plants.1

Women have long been associated with the natural world, often serving as a metaphor for nature itself. Perhaps my hybrid activities outdoors not only represent women relegated to the domestic sphere in the nineteenth century who were engaged in genteel activities that enhanced the atmosphere of the home through décor, music and embroidery. Maybe I was also onto something else that might help illuminate our complex relationship with nature and its connection to the domestic, an arena where women might have the chance of exerting control over their own representation.

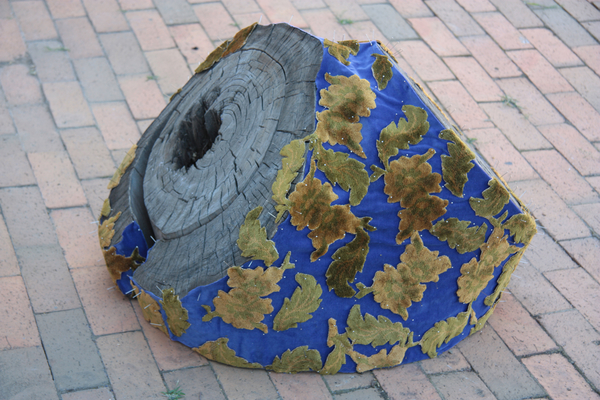

We are in awe of the natural world around us yet still need to maintain dominion over it. Have you ever thought closely about the home and the number of representations of nature that can be found there? In an attempt to bring nature inside, there has been a long history of domestic textiles adorned with flowers, leaves, trees, birds and other images of nature. Might this be a more passive approach to engaging with nature and perhaps a less destructive one? Once the home has been obsessively decorated with images of nature, what next? The only place is to go is outside. What does it mean to wrap the large exposed roots of a huge old lime tree with antique French upholstery fabric? The images on the cloth are of nature: leaves, plants and vines. The blood red colour of the material covering the roots begins to describe a circulatory system. Decorating is taken to the extreme upon upholstering the dead trunk of a holly tree that has regenerated on each corner of the stump. Titled Trône (French for throne), it is indeed a regal seat topped in velvet with a rich fabric patterned with Acanthus leaves wrapping the trunk. Situated within the cultivated landscape, these works become images of nature upon nature within nature.

The works in Folly were created in response to the Château Mathieu residency and they take yet another circuitous turn. Room for One is the first of two furniture pieces that brings raw nature back into the domestic salon. A single wasp-sized nest graces the back of this small Victorian chair, and a weathered branch serves as a makeshift arm. Inspired by small watercolours of ladies in kimonos found at the estate, L’Orient explores ideas of exoticism. The fascination with other cultures was common at a time when distant travel was just beginning. L’Orient is an ottoman upholstered in an Asian-style toile. Toile refers to the cotton material first printed in seventeenth-century France using 10” square wood blocks carved with pastoral scenes and printed with just one colour of dye, either red, blue or black. From the centre of this footstool a lilac branch springs upward. The intricacy of the branch references both the human circulatory system as well as the controlled growth of bonsai trees. The final piece Bloodline returns to similar ideas found in We All Fall Down. An antique christening gown, a woman’s sheer dress shirt that has been tenderly mended, baby bloomers, a silk handkerchief, a stained lace tablecloth are all attached loosely together. Throughout these garments and linens a fine line of blood red embroidery thread connects them: linking them to the Château Mathieu’s history and its matriarchal lineage.

1 Sadie Plant, Zeroes and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture, (New York: Double Day, 1997) 239.